Dear readers,

Since many of you are new here, I thought it was an apt time to properly introduce this publication, Penelope’s Loom — where it came from, and where it’s heading. This is a life project, many years in the making, that pursues Quality. It is a project to be lived and developed slowly over time, in both word and craft; on the loom of life, motherhood, daily duty, as much as in the creative process of weaving which I have been called in recent years to practice…

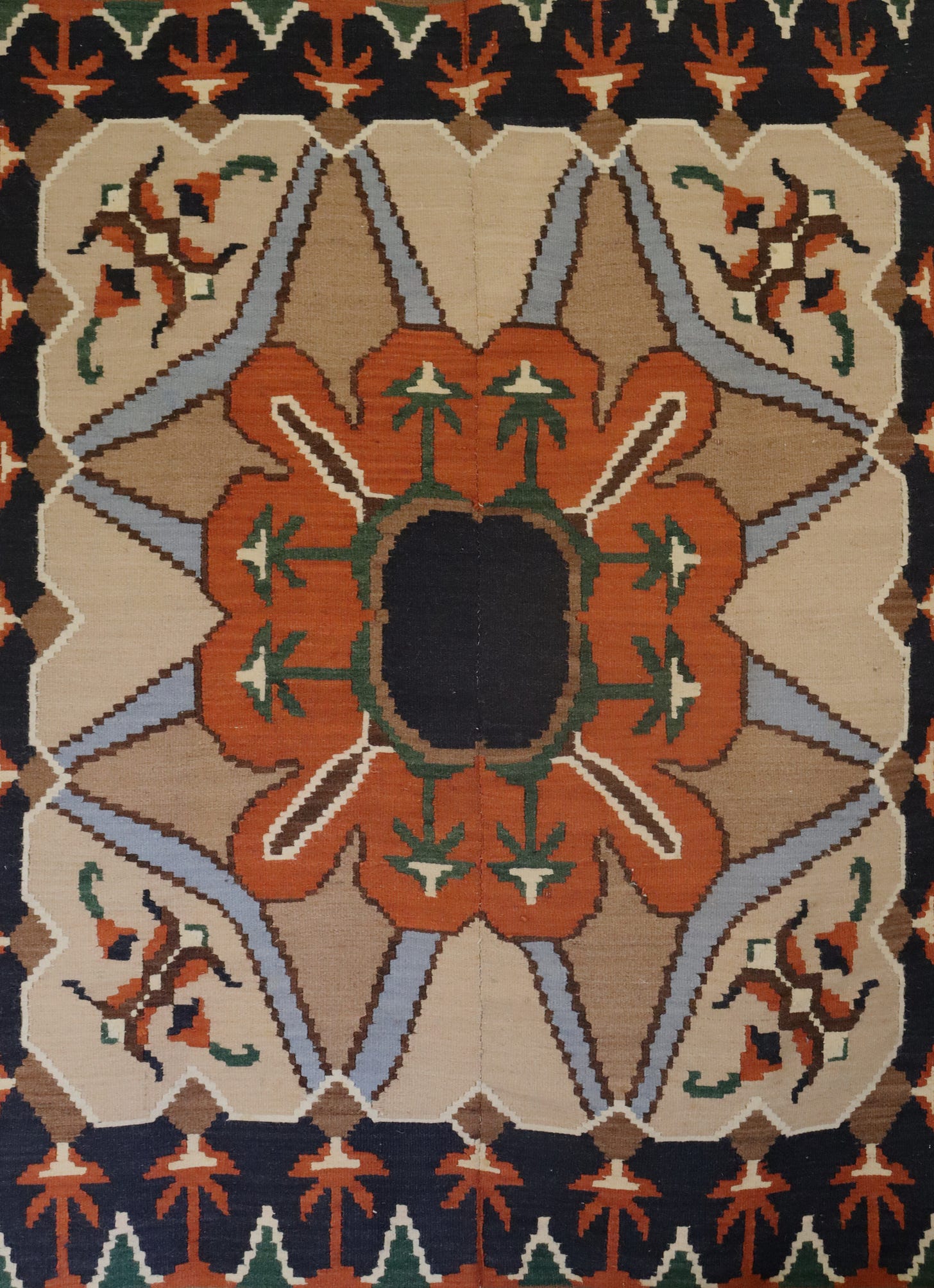

The rug from Arachova

In a shop on the slopes of Arachova, just East of Delphi — Greece’s mythological heartland — my fiance bought me a rug. There it hung, with a kind of subdued glory, quiet but firm in its total superiority to all that surrounded it: machine-spun mats and towels and shawls; mugs and magnets and key-chains; all-manner of sad and sunken souvenirs propped up as signposts to heritage, or its absence.

Like so many shops in the tourist’s playground that is now Greece, my ancestral homeland, this one provoked immediate underwhelm. Filled to the brim with ersatz replacements for Quality, I felt the kind of complete and guttering disillusionment I feel when walking the alleyways of Plaka up to the Acropolis in Athens: these parts that were, not so long ago, home to the real, full, layered lives of Athenians. Now they are flat and lifeless — the revolving mirrors of a grotesque and aimless “sight-seeing”. Reaching the summit, the Acropolis, you find so many screens and selfie-sticks and hind-sides in the way, that you can barely glimpse the columns. What can you do, then, except tick off in your mind the vague notion that something of significance is supposed to be here, right before you; and here you are, supposedly right before it. You may as well take a photo, so you can remind yourself later that you really saw it — the Parthenon.

The dissonance of this place — a place so immense, so steeped in historical brilliance, but now so brutely prostituted to the whims of a base and unchecked tourism — never fails to devastate me. It’s as though we cannot handle the true gravity of its creation, of what heights a culture must reach to produce such a thing of beauty, because it reminds us that we are now so utterly incapable of matching its Quality. Our collective incapacity to create Beauty, not least beautiful architecture, is such a tragedy that we must suppress any vestiges of the past that remind us of the fact. And so in the very midst of utter brilliance, we pull out our iPhones, and with a tap, reduce the monument to square of pixels.1

But in the rug shop on the cliffs of Arachova, I was in for a surprise. Suspended more for display than to tempt the impulse-buyer hung the rug that, an hour later, my fiance would withdraw 500 euros from a nearby ATM to pay for. An hour later, because we stood marveling, discussing, and reflecting on the rug, while countless others stepped in and tapped out with their cheap and lifeless “made-in-Greece” paraphernalia.

We discovered that the rug was hand-woven by the shop-owner’s grandmother, over half a century ago; its yarn hand-spun and brought to multi-coloured life with walnut husks and other botanical pigments from the local surroundings. We discovered that this rug had been hanging there on the wall for 12 years — twelve years, and not a single soul had been roused enough by its beauty to make it their own.

I, on the other hand, felt utterly blessed by the opportunity — not only to behold the rug, but to bring it home with us to Australia. A piece of my heritage, but also, a testament to our human capacity for greatness; a testament to craftsmen and women, to the hands that pull the raw stuff of nature into thread and, that thread, into tapestries of human accomplishment that pay homage to God. A handwoven rug of pure wool stained by its surrounds — a material that condenses in its being days, weeks, months of devoted labour; a material that speaks of the union of body and mind, of Man’s intersection with Nature, and of a deep reverence to land and locality.

This rug was a gift from my fiance, to me, in a very special place, during a very special period of our lives. It was a gift deeply considered: one whose price went beyond our typical means, but one which was nevertheless worth every cent. Everything about this rug, its materiality, its history, but also the way it entered our lives, is special.

It now hangs in my studio at home, a reminder of the importance of Beauty in a world of ugliness; the importance of Goodness in a world of gimcrack; the importance of Truth in a world of deceit. The importance of our embeddedness in the natural world, our dependence on it, but also our capacity to transmute its offerings into Art.

This rug is Quality made manifest.

What is Quality?

“There is a central quality which is the root criterion of life and spirit in a man, a town, a building or a wilderness. This quality is objective and precise, but it cannot be named.”

— Christoper Alexander, A Timeless Way of Building

For many years I’ve been enthralled by a pursuit for Quality — for things, places and experiences that are truly good and beautiful; for spaces that feel alive; for objects and artifacts that enliven the people and things around them. My pursuit takes both a practical and a discursive form: the first, by sourcing the best quality goods and experiences accessible to me (seasonal and pastured produce, handmade furniture and textiles, naturally-fibred clothing, spaces with soul and living ambience, travel that is properly embodied in place and culture, etc.); the second, by trying to articulate and develop what it actually means for any of these things to be “of Quality” in the first place — and how we can know this.

My search for Quality, for the Good, the True and the Beautiful as made manifest in food, fibre, family, space and experience — is in fact my search for God. My parents are of the Orthodox Greek tradition, but while I was baptised in Greece as a kind of family custom, I was not raised with the rites of religion, nor with any understanding of scripture. In fact, my parents were married by a celebrant in a park in Australia, and even my pappou (“grandfather” in Greek) tended to deride God and religious authorities in his anecdotes about his upbringing (to an extent, this was understandable, as he was raised in an insular town on a mountainside in the northern Peloponnese, likely with some overly rigid and corrupted religious practices). Despite being sent to a nominally religious school, the general consensus around me as I came of age in the secular/progressive circles of metropolitan Melbourne was that religion was only acceptable as a peripheral attachment to things, like a flourish around the edges, or a mark of heritage. The “products” of religion, like choir carols, cathedral architecture, or religiously-affiliated educational institutions, were worthy of admiration — but the beliefs and practices they grew from, not so much.

Perhaps because I was denied any acceptable refuge in God by the cultural standards of my upbringing, in my mid-teens I found instead a deep and enduring consolation in the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche. Though he was supposedly the “anti-Christ” proclaiming the death of God, I saw in his work not primarily a nihilism, but a keen appreciation for truth and beauty. Nietzsche was not actually a nihilist, you see — he spoke quite confidently of truth but showed how consistently and cleverly it was concealed. He rejected epistemological dogma, in theology and science alike, forever exposing the over-simplifications we use to avoid contact with hard truths. And yet, his work is fundamentally an affirmation — expressing an exemplary amor fati2 — and it was exactly the affirmation I needed to pull myself up by the hair from the swamp of my secular, postmodernist upbringing. (I’m aware that Nietzsche is in certain ways a progenitor of postmodernism, but I think this owes as much to the misunderstanding of his work as it does to its comprehension — a topic for another time).

As I broke through into my twenties, I relied less on late-night Nietzsche reading sessions (though he is still my intellectual hero), and more on opportunities to use my eye for quality products and experiences as a way to express piety — a kind of worship. Some may cry idolatry, but seeking and selecting quality in our everyday lives (the food we prepare and eat, the clothes we make and repair, the objects we fill our homes with, the relationships we cultivate with the land and with each other) is in fact a very sincere affirmation of God because it acknowledges that there is, in the first place, a firm measure of Quality, of Truth and Beauty — and this necessarily partakes in an ultimate Good (God).

Selecting a unique rug hand-woven on a loom by women who also dyed and spun the wool by hand — in lieu of a polyester rug spun off en masse by a machine — is an act of piety. Preparing a meal from-scratch for your family, with vegetables grown locally or in your very own garden, with meat that was pastured in alignment with ecological health and not to its detriment — this is an act of piety. Doing groceries at a community-run wholefoods collective that supports local farmers and encourages embodied practices of consumption — instead of partaking in the dehumanising physical and ethical structure of a supermarket conglomerate — this, too, is an act of piety.

When I rely on my general sense, my nose for goodness and beauty, I find it easy to locate quality products and experiences, and to fill my life with them. Quality has a charge, and when we have a real appetite for life and meaningful living, we draw Quality easily into our orbit.

But when I sit down to articulate exactly what Quality is — here, I meet a roadblock.

Quality is very real, but it is not a thing. Because it is not a thing, it evades definition.

When we consider something to be "of Quality" it is because it participates in a pattern of relations that promotes Life (where life does not simply mean the mechanical functioning of an organism, but rather an intensity of goodness, truth and beauty). Enlivening patterns are patterns that create continuity between the natural and human world, between the body and the mind. They are patterns which promote wholeness. This means that Quality dwells more in the relations between things than in the things-in-themselves…

Fresh, organic, seasonal ingredients cultivated and harvested with respect for ecological health might go a long way in explaining why a meal is good — but a good meal is ultimately not reducible to its ‘material’ components. What of the manner of its preparation: was it made with care and love by a mother for her children? What of the manner of its consumption: was it shared in good spirits, with good company and wholesome conversation?

On the other hand, a hunk of commercially-made yeast bread of ultra-processed bleached flour is the result of poor-quality patterns of production, of processes of agriculture and industry that generally lead to degraded quality because they do not promote nor revere living systems. But if this hunk were to be shared with a neighbour, in a context of scarcity, those negative energetic charges would be sublimated into an ultimate Good.

Likewise, a teddy bear crocheted in acrylic yarn by grandma and stuffed with polyester might in a material sense be of lesser quality than an organic merino wool comforter from an eco-store, but the spirit in which the teddy bear was made and gifted, and the attachment the child may develop to it, complicates a clear-cut assessment of its “lesser quality”.

Naturally-derived fibres and materials that are processed by human hands rather than machines are far more likely to result in a garment or piece of furniture that is of high quality, because those products will carry with them the enlivening charge of their derivation (Nature) and production (human-scale, humane). But still, the quality of the finished product is a living thing that can’t be captured by a fixed set of properties. Quality is in motion — it is a pattern of relations. Tracing that pattern is difficult.

In our family, we are very intentional about clothing our daughter with natural fibres and supplying her with non-toxic, high-quality toys and bed linens and other childhood paraphernalia. We use cloth nappies because we believe something so full of life as a baby deserves to be wrapped in fibres that are also beautiful and alive. But to be rigid and uncompromising about this approach would actually jeopardise our daughter’s broader access to quality in life: will we reject or dispose of every single gift that contains synthetic materials? No, because it is likely that at least some of those gifts will carry into her life the spirit of love, generosity and good intention with which they were purchased or made and delivered to her by relatives and friends.

Will I reject any meal offered to me that is not made of top-quality pastured meat or organic vegetables? Of course not. To do so would be anathema to the real nature of Quality living — which has at its core, interpersonal connection and communion, like that experienced in the offering and grateful acceptance of food between neighbours. When I lived in Morocco, completing my Arabic language studies (I am somewhat of a polyglot, something you may not have known about me), I was fed daily by a local host family whose quality of living had been greatly compromised by the rapid and unequal globalisation that has ruptured the country. They were a family of few means and while they retained many of the skillsets of a productive household — cooking and preserving and bread-making, for example — the ingredients accessible to them were more often than not of poor quality, including cheap imported meat (the production of which I would not want to see). In spite of all of this, my meals were consistently delicious and satisfying. Why? Because they were prepared with love and care but, even more importantly, because they were always embedded within a web of family and community relations. The food was always shared with others, often from the same plate, and consumed within an atmosphere of conviviality and togetherness.

Another case in point: my daughter has a toy lamb made of synthetic fibres. This lamb is from my own childhood — it was my most beloved toy. It is called “Lamby”. Lamby went with me everywhere. Lamby went on aeroplanes across the world, got lost in an airport, and was found with tears streaming down my face. Lamby got sullied and ragged and went through countless wash cycles. Lamby lost both ears and had them stitched back on by my mum. The ears now point in odd directions. Lamby, while stuffed with synthetic fibres, is nonetheless full of life. She is the stuff of story and memory. I kept Lamby to give her to my daughter — and my daughter, so far, is rather fond of her. How do we assess the quality of Lamby, in this scenario?

Quality is real, but it is not a thing…

To believe Quality is reducible to fixed material entities leads us astray. This is the belief that allows big industries to fool and deceive us, because if Quality is a ‘thing’ and that thing has a ‘label’, it can be sold to us without the proper context of relations that really make it good. This is what a supermarket franchise does when it co-opts the term “organic” and sells us its own patented home-brand "organic” vegetable range — tasteless and lifeless produce grown on water and packed up in plastic. This is merely an imagistic copy of what genuinely organic/biodynamic and regenerative agriculture produces.

But just because Quality is not a thing, does not mean it is endlessly relative. Quality can be flexible and subtle, nuanced and varied, but it is also robust and objective, cohesive and enduring — like a piece of hand-woven cloth.

“We have been taught that there is no objective difference between good buildings and bad, good towns and bad… The fact is that the difference… is an objective matter. It is the difference between health and sickness, wholeness and dividedness, self-maintenance and self-destruction… But it is easy to understand why people believe so firmly that there is no single, solid basis for the difference between good… and bad… It happens because the single central quality which makes the difference cannot be named.”

— Christopher Alexander, The Timeless Way of Building

Penelope’s Loom

Penelope’s Loom is my attempt to bring these realities and ambiguities of Quality more clearly into view. It documents my attempts to affirm God through the smallest, everyday choices, and not only at those critical junctures of my life. This no doubt involves a celebration of seasonal food, sourdough baking, natural fibres, handmade rugs and garments — but also an engagement with the difficult and ongoing work of parsing out exactly where Quality transcends material entities. Family life is central to my pursuit, because the lifeblood of Quality is connection and inter-relational living. For these reasons, Penelope’s Loom will continue to cover a rather large spread of topics, all united by the thread of Quality:

from-scratch cooking, baking, fermenting, preserving

seasonal living and eating

motherhood, birth, pregnancy, child-rearing

domestic management / productive household happenings

natural fibres, handmade clothing and textiles

traditional crafts and trades

my personal journey into fibre crafts (with a focus on hand-weaving)

familial and marital relations

embeddedness in land and community

reflections on the seasons and the natural world

spatial analytics (phenomenological accounts of architecture, interior design, the built world)

theoretical developments on Quality, womanhood/femininity etc.

ὑφαίνω: 1) to weave, 2) to scheme craftily, 3) to compose, write

The publication is named after the Homeric figure of Penelope, Queen of Ithaca, wife of Odysseus and industrious hand-weaver. This is not only because I share her name and have heritage from the Greek island of Ithaca, but because her myth embodies the dual symbolism of weaving both threads and words, of crafting beauty and truth, which is at the heart of my project.

For many years I felt an intensely strong pull towards this craft. Unlike other interests that come and go, the idea of weaving was something I could not shake. In 2022 I got my first taste as a friend in the hometown of my great-grandfather in Ithaca taught me to spin and weave wool from her own sheep on a hand-made tapestry frame. Last year I had another two opportunities to learn from experienced weavers back in Australia: on both a Saori (Japanese) freestyle loom, and on a rigid heddle loom. This year, finally, I have gotten my hands on a beautiful, very wide 4-shaft table loom and have just finished a more comprehensive introductory weaving course. As I write this, I am in the process of starting my very first rug on said loom: to honour the spirit of the rug from Arachova which has become the central symbol and logo of Penelope’s Loom.

There is so much more to say about the mythos of Penelope, her central role in the Homeric epic of the Odyssey, and her work at the intersection of material, social and narrative craftsmanship — expect this to feature in future essays. For now, I will leave you with a passage from the Odyssey, detailing the craft, both material and discursive, which Penelope employed to stave off the forces intent on rendering apart her marriage and family:

So they urge on marriage, and I wind a skein of wiles. First some daimōn breathed the thought in my heart to weave a garment, after setting up a great fabric in my halls |140 fine of thread and very wide; and I straightway spoke among them: “Young men, my wooers, since godlike Odysseus is dead, be patient, though eager for my marriage, until I finish this garment—I would not that my threads should perish useless—a shroud for the hero Laertes against the time when |145 the fell fate of grievous death shall strike him down; lest any one of the Achaean women in the land blame me, if he were to lie without a shroud, who had won great possessions.” So I spoke, and their proud hearts consented. Then by day I would weave the great web, |150 but by night would unravel it, after having placed torches by me. Thus for three years I went unnoticed and persuaded the Achaeans; but when the fourth year came, as the seasons rolled on, as the months waned, and many days had revolved, then verily by the help of my maidens… |155 they came upon me and caught me, and upbraided me loudly. So I finished the web against my will perforce. And now I can neither escape the marriage nor devise any counsel more. [3]

…

|145 And we caught her while she was unraveling her splendid fabric. So she finished it against her will, perforce; and when she showed us the garment after she had weaved it, after she had had it washed, similar to the sun or the moon, right at that time some malicious superhuman force [daimōn] brought back Odysseus.3

The loom for me is both a physical apparatus of weaving and a schema of mind and spirit through which to reach God. As I pass my shuttle back and forth through the warp, interlocking fibres to reveal a length of cloth, so I want to weave words that bring truth slowly into view — a truth strong but supple, tactile but transcendent. A truth like woven cloth: robust enough to endure in time, but flexible enough to drape with grace the contours of the human body and the shapes of our world.

Supporting the pursuit

Lastly, I have recently decided to open up paid subscriptions. If you feel called to support my project, that is now an option for you. Otherwise, I want to thank all of my readers, especially those who have been following along from the very beginning (you know who you are), and especially those who take the time to comment and respond to my essays. Comments are my favourite things — moreso than subscriptions, moreso than likes and view counts. I always want to hear how my ideas land with you, how they resonate or how your views may differ or compliment and complete my own. Thank you to those frequent commenters for their sincere engagement, it really means a lot.

The implication of really seeing and feeling the Parthenon’s significance would be a proper reckoning with our current collective paralysis surrounding Quality; with our lost capacity, not necessarily as individuals but as a culture and civilization, to produce monumental beauty.

Love of fate.

https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/penelopes-great-web-the-violent-interruption/

I so enjoyed reading this!

It's something my husband and I have discussed a lot, too. I am OBSESSED with quality, but am perfectly aware of how I can be tempted to go too far at the cost of Quality Living as you say. I have a polyester baby sweater crocheted by my great-grandmother -- I simply can't get rid of it though. Because although I am a little snooty and think crocheting is inferior to knitting, and polyester is toxic, I can't help but remember that so many relatives wore it and why should I deny that to our child? I also have a couple baby dresses from my grandmother that I'm certain are synthetic. But again -- my uncles and aunts wore them. I want our children to not watch TV... but when they go to Grandma's house, I don't want them to feel like they can't watch it with her. I think of my grandparents who eat organic only food, who wear the best clothes, who have the best for everything. They talk about how long their lives will be and the quality of their health. But they will never eat at any of their children's homes, they rarely have guests over (the food they serve is pricey) and they turn down all dinner invitations. And so they have no communion with anyone. They have gone to none of the family's weddings, etc. They are not in any of their children's or grandchildren's lives because what would they eat if they traveled? And they wouldn't be able to sleep on the best, quality bed since they own that at home. And so they have extended their lives in the pursuit of Quality, but they are lonely. I want to have a balance for our children and our home -- a place that is comfortable and beautiful and filled with true quality things, but also brimming with laughter and life, and able to share in that in other homes with other people.

I love that loom, too! And the basket of yarn is so satisfying! I had a rug loom, but wasn't able to move it to Upstate New York. I would love to get into weaving, so maybe I'll get it up here at some point. But I think I'm going to try and master spinning first this winter.

Wow I had chills the entire time reading this. Nietzsche was also the hero of my youth and if you haven’t read the Sue Prideaux book “I Am Dynamite” on his life I think you would absolutely love it. I also completely dissociate at the tourist hellsites in Athens. My father-in-law grew up there and I’ve been lucky to see all the secret corners of his youth but surviving the Acropolis is a whole different story. I have to just force myself to make drawings and try and ignore the hoards of incredibly rude people. Because my husband is fluent in “old” Greek (like the equivalent of formal early 20th century English) that his grandparents spoke to him we are treated well even in the worst parts, including our much-dreaded trip to Santorini with my Australian TOURIST grandmother! It’s so important to us that (our) Penelope learns Greek so I’m learning too.