There is one sight that never fails to rouse a wellspring of feeling in me: a man of my grandfather’s generation, suited up with the kind of modest but meticulous attention to detail and cleanliness that, nowadays, we barely reserve for special occasions. This man is merely walking to the shops: leather shoes buffed and shiny, shoelaces pulled taut, pants and jacket freshly pressed, face groomed and hair combed beneath a woollen flat cap. He moves through space, not looking for attention, but prepared enough that if someone were to lay eyes on him, he would be a pleasing sight to behold.

This is what I think of as the middle-ground of vestiture: dressing and composing oneself in a way that positions you somewhere in between fixation and disregard. You're not so presumptuously dressed so as to centre all lines of sight on you, but you're also not so slovenly that people feel the need to look away, nor so indifferent in your presentation, that people don't catch sight of you in the first place. Neither pompous nor withdrawn, but neat and agreeable.

Looking at these people is a kind of quiet acknowledgement, a sigh of relief: that someone still cares enough to make their beauty and goodness manifest. That someone harnesses their appearance neither to conceal evil, nor to render it irrelevant as a signpost for that which lies beneath — but to show that it can be a genuine outgrowth of a well-furnished interior.

These days, such presentation seems to be limited by age. It is usually exhibited by the men and women of my grandparents’ generation, and to a lesser extent of my parents’. Outside of this bracket, it is increasingly rare that someone’s garb will rouse such admiration in me. The few times this has happened have stayed with me in vivid form: I remember also a woman, in her 30s, immaculately dressed, in garb feminine and befitting, modest but alluring. She wore a knee-length female suit-skirt and jacket, tailored to her figure, a pair of classic heeled mary-janes, polished to perfection, and had her hair pulled with painstaking neatness into a bun. She reminded me of the sartorial diligence of air hostesses. I kept her image with me as an aspiration as I grew into womanhood.

These sights stir my nostalgia, partly because I know that the grace they exhibit is fading away with the generation still practicing it as a habit. In what follows, I’d like to explore some reasons why.

There are masses of literature on the many and complicated linkages between vestiture, etiquette and class. This does not command my immediate interest. What I want to understand is why the basic all-too-human desire, but also duty, to present gracefully and appropriately in public often feels like it’s on the out. I disregard the classist analysis because today, often the most affluent present themselves with the least propriety; while the humble, agricultural families of my grandfather’s home-village in Greece, for example, dressed not so long ago (and its elders still do) with the quiet charm and poise described in the opening of the essay.

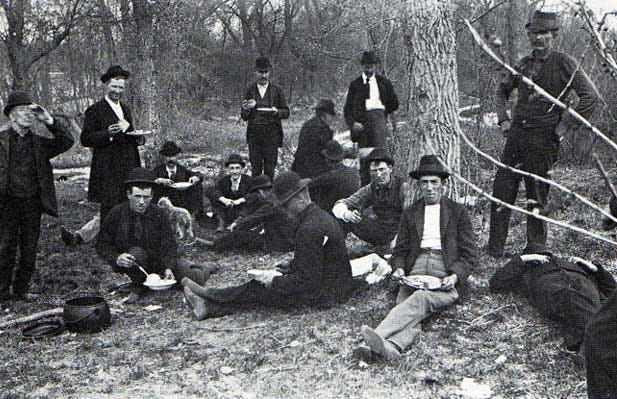

recently made a similar observation:“Kind of incredible to me that most homeless people of the past dressed more nicely than the regular, ‘respectable’ people of today.”

The following image was attached:

I’m not the first to note or decry the casualisation of dress and appearance — and I have been guilty of it myself. Feeling free to walk to the post office in stained track-pants and greasy hair thrown up in a scrunchie last-minute no doubt has its benefits. Feeling free to use dress as an outlet for experimentation and transgression also has its place. But the substrate of social expectation and perception which now supports this as a norm rather than an exception has more dire implications than arousing the distaste of those queuing alongside you to send off their parcels. Below are my rough thoughts on the causes, and consequences, of this demise of decorum.

Relativism & Loss of the Centre

I’ll start with perhaps the most obvious and least enlightening reason: in a culture largely unmoored from any fixed standards of goodness, truth and beauty — one that raises children to believe that beauty is always and invariably “in the eye of the beholder” (however positive such a belief can be) — it is rather difficult to make the case that some standards of public decorum are better than others. Like high-school students flouting the dress code, we resist any pressure that might be stronger or more enduring than an Instagram trend to conform to standards of propriety, especially when they are perceived to come from “above”. In reality, basic codes of propriety develop tacitly over time, in the general interests of the community, and are only sometimes and secondarily “imposed” in explicit or extreme terms by authorities.

Those who dare to suggest that some standards of value are beyond the particularities of culture and the whims of individuals, risk being branded “fascistic”. All-too-aware of the real historical consequences of fascism, while often entirely inconsiderate of the appropriate contexts for its modern comparative use and allusion, we fearmonger each other into believing that ideas of “goodness” cannot be firm and objective without being oppressive.

Nonetheless, it is obvious to me that there are some timeless principles for good public etiquette cross-culturally, while certain principles might be emphasised more or less in certain cultures. These are: modesty, cleanliness, aesthetic harmony, a context-attenuated discreetness in voice, action and manner, a certain selflessness in dealings with others, as well as self-control and reserve in the interests of public order. (These apply, I think, to human communities whose scale transcends the tribe; from village to city, where individuals will have public interface with other individuals to whom they would not expose the privacy of their domestic lives.)

All of these principles have in common a refined consideration of the boundaries between self and other — not complete estrangement from the other, nor total divulgence of self, but a balance between concealment and exposure. A kind of moderate self “veiling” in dress and mannerism can actually facilitate deeper connection in the long-term, sabotaged in both instances if we are either too prompt to reveal our full selves, or otherwise too apathetic or withdrawn from sight.

Postmodern society has lost this balance between self and other. It is instead strung out between the extremes of mask-wearing social distancing and naked body-positive protesting. We are over-exposed but under-connected. And despite suffocating in a straight-jacket of political correctness, we are actually not very polite and proper anymore. We have lost mastery of the middle, the mean, the moderate — perhaps because we are obsessed with dislodging the majority for the minority; obsessed with denying the average but emphasising the anomly; obsessed with bringing the margin to the centre.

A recent example from Substack was a post by

that advocated eschewing the greeting “How are you?” in the supposed interests of greater “authenticity”. Here’s an excerpt:“How are you?” is the most weaponized phrase in the English language

It’s a Trojan horse of politeness, forcing you into a dull, predictable lie: “Fine.”

So go nuclear. Don’t just answer. Detonate.

…

Why? Because breaking the script shatters the illusion that “fine” was ever an answer.

People won’t step back. They’ll lean in. Desperate to escape their own loop of lifeless exchanges.

As I said in response to the above: thinking one has the right to forgo social graces and rituals of public decorum is another level of narcissism. It belies a juvenile and saccharine view of authenticity which assumes that all pleasantries are shallow rather than integral to public order. It also reflects the general inversion of inter-personal ethics whereby you are no longer required to prove yourself through social presentation but rather the onus is on other people to give you the benefit of the doubt because, “underneath”, you are an immutably good person which you needn’t prove by means of appearances (more on this later). Sometimes, though, the outer shell is an authentic expression of inner goodness, like when people care enough about others not to dump their private lives on them at the first greeting. As

rightly noted in response to the same post:“There is an important and intricate social dance that needs to happen before you can be sure you have permission to unload emotionally on someone who has just greeted you. Most of that takes place tacitly. Presuming on your right to short-circuit that is incredibly rude and selfish.”

The same kind of affected, exaggerated approach to interactions with strangers that Kuriakin promotes is demonstrated by those that skip a handshake for a slightly too long, slightly too intentional hug with a new acquaintenance — ostensibly in the interests of greater “connection”. I will never forget the time my well-meaning but self-absorbed 17-year-old self opted in to an eye-gazing session run on the streets of the Melbourne CBD by the so-called “Human Connection Movement”. I sat myself down in front of a complete stranger and gazed into her eyes for a full 5 minutes. No exchange of words was allowed; locking eyes was apparently all that was needed to forge a deep relation. I found this remarkably difficult as I had no idea which of her eyes to look at and so jumped left and right with my gaze, all the while trying really hard to tap into the tantric field of inter-personal resonance I was promised. At one point, my eye-locuter broke into tears (did I do something to offend her?). I must confess, I never felt a thing — though I really, truly, tried (God bless my teenage soul).

Attitudes that promote transgressing the social dance of handshakes and small-talk show not only how we’ve strayed from temperance to trigger-happy divulgence, but also cast light on our collective paranoia that all social conventions are reducible to power dynamics. Kuriakin’s post explicitly deploys the language of power, claiming that rituals of polite greeting and small talk are “weaponised” and that, in response, we should make greater specificity our own “weapon” in counter-attack. According to him, we should not say “I am fine, and you” but rather “I’m two bad decisions away from Googling ‘how to fake my own death.’” Why? Because politeness is apparently designed to oppress us, and we should re-appropriate its discursive weapons to our own advantage… This leads nicely to the next point.

Paranoia

We are the heirs of an intellectual “tradition” which assumes, mercilessly, that to get to the core of something — a person, an act, a literary text — we must mine into the innermost depths of its psychology. We carry a general paranoia that appearances always belie something dark and sinister; that what underlies appearances must necessarily negate them; that we should therefore do away with appearances all together. But also — an ironic inversion — that we should always be able to find goodness within things that seem outwardly ugly or evil. In other words, things that appear to be good, we deem substantively evil (or at least, never as good as they “seem”). Things that appear to be evil, on the other hand, we like to give the benefit of the doubt that they most probably contain some goodness, on the “inside”.

We see this paranoia play out in the radical-feminist mistrust of aid offered from man to woman in the opening of a door or in acts of giving-way — that this is somehow either sexually suggestive, or otherwise a pernicious signal of the assumed fragility of the woman. We see it also in the social activists’ disdain of monuments, architectural or cultural, that they see to be invariably propped up on the backs of the oppressed and exploited, whose suffering they conceal. Lastly, we see it run rife in academic contexts, where students are taught to apply feminist, postmodern, post-colonial, post-humanist, post-whatever analyses to all manner of subject matter and reduce great works of art and beauty to bleak accounts of power.

I chalk this up mostly to the pervasive influence of psychoanalytic intellectualism, which has trickled down from the “think-tanks” of modern academia (if you’ve taken an English literature subject at the tertiary level and were dumped on by the lecturers and readings with Lacanian drivel, then you know what I mean). Psychoanalysis has its immense boons, I barely need to qualify. But when inculcated as the default approach to interpreting phenomena it often severely misses the mark — or otherwise, inflates an interpretation that, while perhaps partly valid, robs the phenomena of its broader context, beauty and depth. And this is the paradox: by setting out to bore into the psychological “depths” of something, we ironically end up eviscerating that thing of its fuller and more complex reality.

In the same vein, we’ve been taught that people cover up deep issues with deceptive garb. This is, no doubt, often true. But we’ve forgotten that often — and indeed, almost aways, for the sufficiently discerning — a genuinely beautiful appearance grows out of a healthy interior; as the flower of its seed. And if we abandon regard for appearances, either by means of paranoia, mistrust or some kind of perverted righteousness, we end up trading in other kinds of deception, like the kind which claims that goodness and beauty can only be found within and therefore have no public face or extrinsic standard; or worse, that they will always be found within (on a similar topic, see

, “Evil is not a Mental Illness”).The pathologisation of shame

Disproportionate shaming can be acutely damaging, but the solution is not to forgo shame altogether. As a kind of social homeopathic, small doses of shame can be incredibly healthy and productive. We are, these days, much too fragile in the face of disapproval and critique. A case in point: an Australian university recently changed their post-doctoral protocols so that their progress evaluation meetings no longer include any kind of rigorous questioning of the thesis — apparently because one such instance had made a student cry. When we do away with the possibility of shame, we also threaten aspiration and acheivement. When we do away with the risk of offense in dialogue, we threaten truth. Another irony: we are far more willing to offend others in dress and public presentation than we are to risk offense in contexts of knowledge-production, where it actually matters.

We should embrace a sense of shame if we realise after leaving the house that our skirt is too short, or our pants reveal an oil-stain, or our breath smells… Most of us still do, thank God. But these are easier examples to countenance. I think there is value in a more general self-consciousness of the things we can now typically get away with: overly casual dress, slovenly hair, slipshod shoes, unclipped nails, straggly nose hairs, exaggerated tones of voice on public transport, phone-glued-faces while walking the streets, etc.

I would not be surprised that if our presentation in the public arena were treated with more apprehension, diligence and reverance, the ease and comfort of our home lives would deepen in contrast. As we can see, the blurring of boundaries between public and private space has certainly not correlated with deeper connection, nor greater authenticity.

Rights versus duties

An individual’s right to expression versus his duty to the community is a fine and often unsuccessfully mediated line. But it is obvious that the exaggerated emphasis we place today on individual rights and on self-actualisation in general is part of the story behind our increasingly lax approach to decorum. Collectively we have forgotten that we can actually amplify our individual value by means of cooperative participation in the social whole and by deference to the limitations that whole places on our “freedom”. Perhaps this means at times we must dress and present in accordance with standards of modesty and discretion rather than mercilessly pursue idiosyncratic expression.

In this context, for example, our desire to physically express our lust for our partner in public would be suppressed in the interests of the community, and reserved for a private, more appropriate locale. You would not grow up, like I did, seeing men and women groping and rolling over eachother in public parks where children’s plays are being screened (this could be reserved for less-populated pockets of nature, because who doesn’t secretly love the idea of smooching a lover in the soil). In the case of non-normative sexual acts (and yes, I mean those that deviate from heterosexual monogamy), these would be tolerated and accepted so long as they conformed to standards of discretion and did not impose themselves too patently on public perception. I was raised in one of the most liberal and diverse pockets of inner-city Melbourne, and taught to “problematise” the disgust I felt seeing raunchy cross-dressers set up their slimy sex clubs in broad daylight. I have no interest in policing “consensual” sexual affairs, but maturity has granted me the confidence to opine that these should be kept behind close doors.

This reminds me of an Islamic parable. I can’t remember its source but an Arabic scholar recounted it to me along these lines: a man walking past a dwelling with a slightly gaping door witnessed an unlawful act taking place between two individuals (from memory, it was something sexually-transgressive by the standards of the time). The man proceeded to publicly chastise the pair and make the details of their act known to the community. The parable concluded, however, that the greater sin was committed by the man who made the incident public and thereby spread its influence, rather than that committed by the individuals in private.

Loss of ritualised transgression

Transgression is necessary for the ongoing health of an established social structure. It has a regenerative energy which must be drawn on when institutions ossify and become corrupted. But when transgressive behaviour becomes the norm — that is, overwhelms the status quo rather than being integrated into it — we end up throwing out the baby with the bath water.1 It seems to me that we lack proper rituals for integrating such behaviour in productive rather than damaging ways.

I am not a very industrious student of history, but it is apparent that the great civilisations of the past — when they were flourishing and not falling — cultivated refined structures within which to express ideas and energies that otherwise contradicted social norms. In the Athens of 500BC, the Theatre of Dionysus was one such structure: in the bounds of a drama, normative values were questioned, and alternatives proposed. Identity was rendered an indeterminate process of contestation and renewal. The offensive, destabilising, and outrageous were permitted. This creative commitment to processes, rather than insistence on fixed identities, found incarnation in the god Dionysus — often excluded from the Olympian Pantheon, but widely acknowledged in practice. Classical Athens was a culture that generally valourised masculinity, decorum, discipline, prudence, moderation and self-control (sophrosyne), but through cultural institutions such as the Theatre of Dionysus, it also celebrated the regenerative life-force of femininity, the transgression of boundaries, and hysteric excess or “ecstasy” (ekstasis in Greek, meaning the trance-like rapture of losing or standing outside of the self). The Athenians acheived a remarkable civic order in which volatile and seditious elements were incorporated and embraced without the dissolution of normative decorum.

The art forms of our time also accommodate transgression. Drunken raves accommodate transgression. But in the absence of a more refined, integrative structure, transgression breaks the fourth wall and seeps into contexts of public life where it does more harm than good. Bringing the margin to the centre does not do away with centres — it simply creates a new one. Our streets and screens, the foremost public arenas, have become our canvases; our theatres of personal confession. This is because we no longer have many appropriately ritualised containers for excess and indiscretion.

Inverted standards

As already noted, we live a curious inversion: instead of the onus being on the individual to prove that he or she is good, truthful and beautiful, it has been diverted to others/onlookers to to seek what is good, true and beautiful within the individual — and to go as far in, as deep down as possible to find this worth, or to create it where it doesn't exist. While our culture is mired in surface-level optics, we are at the same time told to mistrust appearances and constantly look deeper.

No one could get away with arguing that a generous, patient, persistent and inward-looking perception of others is a bad thing. This is obviously not my point. Rather, it is bad to mistrust and dismiss the "outside" all-together because it is thought that the "inside" is all the matters. To reiterate: a beautiful exterior can be the consequence of a beautiful interior, not its concealment. We shouldn't exploit the generous judgement of others to become sloths of appearance and mannerism. To the extent of our capacity and control, we should attempt to make apparent the goodness we contain, not in an attempt to boast or virtue-signal, but to allow the beauty we contain to create continuity between the inside and out.

This should actually be easy to do. Dressing well, and maintaing propriety in public mannerisms, should be a natural expression not only of our own self-esteem and dignity but of our concern for the dignity of others with whom we share space (if, indeed, we hold such dignity and concern). It should express a balanced perception of the self — situated within the web of its community. There’s nothing more offputting than boarding a train carriage filled with the screech of another’s TikTok addiction or a raucous phone conversation. This is a plain expression of deficient virtue: a kind of self-absorption and negligence of others and environment. Equally, there’s something refreshingly charming about someone who offers their seat on the bus or sits with their bags pulled tight around them so as to not overexpand their presence in the space.

My generation of women was taught the solipsistic mantra to “take up space” and “be loud”, as though that was an effective way to establish and reaffirm our value. I couldn’t think of anything more degrading and infantilising. There is nothing inherently oppressive about holding the female body in a closed and composed manner — in fact, quite the opposite. Should men dress and hold themselves with modesty too? Absolutely, though perhaps in sex-specific ways. (When people critique veiling practices in the Arabo-Islamic world, for example, they neglect the fact that modest garb is just as much an obligation for men as it is for women. I do not support complete head-to-toe veiling, i.e. face coverings, because I think they have been improperly politicised when they actually derive from the climactic considerations of desert tribes; and also because they are not conducive to interpersonal connections in the public sphere; but moderate veiling practices, i.e. of cleavage, legs and even hair, are in my view very laudable.)

Personally, the periods of life in which I’ve been the most genuinely content, vital and energetically in-tune are those during which I have also relished in proper presentation and in aspiring towards modest beauty. On the other hand, the times during which I put little effort into my appearance — and deceived myself that this was somehow more “authentic” — were times of spiritual, intellectual and physical lethargy, of psychological duress, and of energetic imbalance. In these cases, my appearance was a bona fide outgrowth of my interior circumstances.

I’d like to finish with an example which illustrates the broader malaise of our times. Compare the below two images: the first is a sculpture of the Ancient Greek demi-God Hercules in the botanical gardens of the regional town in Australia we currently call home; the second is a climate count-down “sculpture” in a park in the oh-so-trendy and transgressive neighbourhood of inner-city Melbourne where I was born and raised.

Our relativistic dilly-dallying and our mistrust of beauty has other consequences besides the death of aspiration. In the context of the “climate count-down”, art has been hijacked by narrow political agendas. The “heritage plinth” has been decapitated and made an ugly, self-conflicted and alien kind of hybrid. In such milieus, Art is no longer valued if it champions any durable and transcendent ideal of goodness. Instead, it is valued if it broadcasts a short-fused and isolated social justice agenda. Even better when it expresses solidarity with real or perceived victims and minorities (“nature” being the victim here, as well as “future generations”).2 Good art should certainly deepen empathy and humanity. But when humanitarian ideals are divorced from a more transcendant cosmology, they fall prey to base political exploitation. And when their content is not supported by any kind of formal beauty, they cannot claim the mantle of Art. The very explicit, mono-phonic message conveyed by the “climate countdown” is in fact inimical to Art, which reserves as its essence the expression of truth through polysemy; and though its makers no doubt wear the badge of Diversity and Inclusion, their advocacy is oppressively flat. Perhaps they should apply their own psycholanalytic metrics to the virtue purported on the pedestal. On the other hand, this is exactly how it seems: ugly. Any subculture which produces and allows something so brute and ugly is, I’m afraid, a brute and ugly subculture.

Final Thoughts

If something — a building, a tool, a piece of furniture — is poorly designed and made, I'd rather it be exposed for what it is with no obfuscating wallpaper or varnish. But most of all, I'd rather a thing that's well made in the first place, from its interior to its exterior. Perhaps this is precisely the issue: have we lost, collectively, the virtue from which beauty grows? Are we no longer capable of ornamentation? Not the kind which obscures a rotten core, but which unfurls from inner goodness? Is the ugliness of our times, and the demise of decorum, actually a candid, cancerous outgrowth of our spiritual and moral ruin?

Perhaps it’s redundant to tell people to clean their fingernails, polish their shoes, open the door for others, speak softly in public, be discreet but not apathetic. Perhaps it’s a pipe-dream to wish we could bring back the ladies and gentlemen. Perhaps something much deeper is needed first…

Having said that, I also grant that at certain junctures in history, the abrupt and complete overthrow of an order may be required…

I am an ardent advocate of improved, deepened, more reverant and less extractive interactions with the natural world. Climate countdowns, UN summits and “Extinction Rebellion” stunts are not the way to acheive this, I’m afraid.

I enjoyed reading this insightful article, thank you!

Yes...endorse