This essay was adapted from a research paper of mine in Arabic language and cultural studies, written during my time living with a host family in Morocco. It consists of two parts: the first part outlining the conceptual framework, the second (arguably more exciting) part offering illustrative vignettes that bring this framework vividly to life.

“The thing about Saudi is, on the surface, it seems like men control everything. But in the homes, women totally dominate.”

It was the last thing I expected to hear from the table next to us in a cafe in regional Victoria. And yet, it came confidently from the lips of an Anglo-Australian man, in his 60s or 70s, in casual conversation with a friend of the same physiognomy. I couldn’t help but lean over to chime in: “That’s very true. I saw the same whilst living in Morocco.” They now found themselves with two new interlocutors.

As it turned out, this man had lived for a decade in various countries in the Middle East, posted for his work in telecommunications, including a long stretch in what is widely considered the most “oppressively patriarchal” of them all: Saudi Arabia. It was clear as the discussion progressed that his statement intended not to overlook or justify the excesses of a society far from perfect, but to bring nuance to the facile characterisation of women in the broader Arabo-Islamic region as totally deprived of agency by a social structure that disencourages them from “wearing the pants” in their families and communities — which is to say, a structure which instead supports them to embrace and thoroughly command the powers inherent in the positions they are biologically endowed to inhabit as mothers and matriarchs. We had both come to similar conclusions living in parts of this region that women wield a very real power not readily granted them by the metrics of post-industrial Western liberalism.

“Patriarchy” is one of those terms that makes intelligent thinkers cringe, not because it doesn’t point to a genuine reality, but because it signals a cliche of thought which is anti-thinking and largely obfuscates that reality. It is like a face-mask, worn by the obedient, unquestioning mind, distancing it from contact with truth by blunting smell and sense. The problem with cliches is that they dis-incentivise proper exploration of the topics they allude to. If they don’t dull discernment, they often turn otherwise discerning minds away.

This is a shame, not least because the injudicious use of the word “patriarchy” and its correlates hides a conflation which should be a distinction: that the operation of patriarchal structures does not necessarily imply the complete dominance of men and masculine energies, nor the blanket suppression of women and feminine energies. It can, in fact, provide the necessary conditions for the optimal expression of femininity (of which women are the prime beneficiaries), and prevent its own self-devouring.

My experience living within traditional family structures in Morocco led me to the following cursory thesis: that many of radical feminism’s attempts to dismember and undermine “patriarchal structures” — in morality and sexual relations, as in patterns of work and vocation — have correlated, ironically, with the masculinsation of society, including but not limited to increased atomisation, the privileging of independence over inter-dependence, the asphyxiation of inter-relational patterns of thought and practice and their replacement by conceptions and idolisations of the self and objects as “separate” in their own right, rather than defined by their participation in a web of connections.

What follows in Part 1 and 2 of this essay adaptation is an account of this reckoning of mine, an attempt to unpack this distinction, which crystallized in my mind during months of immersive participation in the life of a Moroccan host family, and especially close contact with the Matriarchs connected to this family. What they taught me — in actions, not words — was that women are empowered when their feminine dispositions are supported, not when those dispositions are undermined by, or conflated with, their masculine counterparts. To see this in action, we need to focus less on explicit structures of governance, morality and vocation, and more on the implicit morphology of selfhood and spatiality that characterises a given society. I came to realise that Morocco, overall, is characterised by what I call a “reticulated” sense of self and space, which is a fundamentally feminine morphology.

PART 1: THE CONCEPT OF RETICULATION

Reticulation: an arrangement resembling a net or network.

I’m roused by God’s alarmclock: Fajr.1 I had dozed off only a few hours before. Guests had stayed late, and khalti2 Naima followed. I am under-slept but not tired. It is hard to be tired here in Rabat, Morocco, where binaries still produce life. And this house oozes with it — life — from its multiple stories, and from the neighbours hugging its walls. Terraced around a central courtyard, it was once the unified residence of an extended family. It has since been repurposed: we inhabit the middle floor, with rooms wrapped around the courtyard-cum-living-space down below, where another family dwells. Their space is concealed loosely from our vantage by curtains, but their movements rise up to us daily, filling the heart of the house with the music of a budding family.3

I melt back into rest for a while, carrying the sweet fatigue of yesterday’s endless interactions. When the aromas of coffee and freshly-made ḥarsha4 seep in through my bedroom door, I know my host mum Najiyya has reclaimed her golden mantle: as mother, as matriarch. This she does as surely as the sun rises each dawn to feed the needy souls of the earth. Her daughter has, to be sure, already married and moved out; but there is Rayān, her grandson, who spends more time here with us than in his ‘own’ house, which is emptied most of the day by the newfangled prerogatives of the working-woman. In his 4 year-old mind, two mums exist — and all the better. It is not just the food on the table he comes for; it is the sumptuous warmth of a home that still sanctifies motherhood. And a mother she still is, Najiyya (نجيّة) confidant, entrusted with the care and sustenance of others, far beyond the maturation of her daughter. Even the birds and plants on the terrace drink from her maternal well. In the kitchen, various nooks home ceramic animal figurines, each with their own personalities, keeping her company as she cooks up life itself. And then there is me, Australian exchange-student, miskīna (“poor girl”), boarding with the family for four months, fed and cared-for like any other, like their own bint (daughter) from day one.

When you visit Morocco, especially when solo, what is noticed first by locals is your estrangement. You are not so much a traveler, gaining new experiences, but a foreigner in the true sense of the word: you have lost something, you are removed from your circle, from your familial and cultural whole. You thus become the subject of well-meaning pity: miskīn, meaning “poor thing”, was the typical reply to news of my origin and status as a visitor. It is related to the verbs (تَمَسْكَنَ tamaskana) to become poor and (أَسْكَنَ askana) to house or shelter. In most swathes of Moroccan reality, a person outside of his home — family, town, community — is more readily pitied than glorified for his independence. But this pity is shortly resolved by the equally instinctual and open-handed desire to embrace and integrate the foreign element into the nearest ‘whole’. These two distinct but indivisible responses are reflected in the verbal cognates just mentioned. Hence the remarkable ease and speed with which a foreigner will be welcomed into the Moroccan community: you will be literally or symbolically ‘sheltered’, invited for tea or board, or simply welcomed by the hug of hospitable speech (marḥaban bik you are welcome, among the most common greetings and synonymous to ‘hello’ in standard Arabic and Moroccan Arabic alike). Drawn back from your wretched isolation, your value is restored.

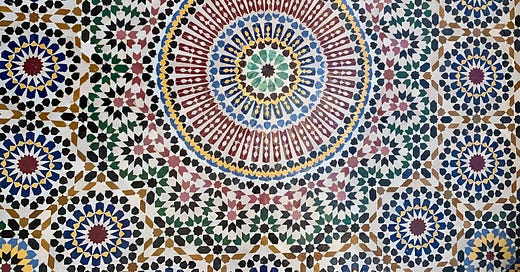

This approach to the foreigner — or, more fundamentally, to any ‘individual’, ‘element’ or ‘thing’ deemed (temporarily) separate from a whole — defines a spatial practice characteristic of Moroccan reality. This is a spatial structure which I came to think of in terms of the concept of “reticulation” — a web or network of relations. It manifests not only in a Moroccan’s relationship to a foreign traveler, but also in the structural layout of their homes, neighbourhoods and cities — especially in the case of the fortified ‘old cities’ that still exist today in Rabat, Fez, Marrakech, Tangiers, and the like. The term is apt because it also describes the net-like motifs characteristic of Islamic architecture and ornamentation.

Traditional Moroccan houses are thought, by injudicious outside observers, to function purely according to a principal of interiority and seclusion, guarding the ‘feminine’ domestic space from the intruding ‘male gaze’. While true to some extent, this view lacks nuance, and is more revealing about the cognitive dispositions of those who promote it. Living with a host family in the ‘old Madina’ (old city, المدينة العتيقة) of Rabat, I was impressed first and foremost by the deep sense of cohabitation and spatial interrelation. When I sat in the lounge, the matron of the home across the alleyway cooked to the hum of the radio, the smells and sounds streaming from her wide-open windows to ours as though a continuation of the one home. When I ascended with my host mum Najiyya to the rooftop to hang laundry, we almost invariably found Fouziya doing the same, our neighbour to the rear of the home. The two matriarchs would chit-chat or exhange baghrir, Moroccan pancakes, for harira, Moroccan tomato soup, across the roof partition. In all directions: above, below and across, my host family’s home-space overlapped that of its many, and intimately-known, neighbours.

These are just two examples of the everywhere observable interdigitation of so-called ‘private’ spaces in the old Madina — examples which will be fleshed out and more colourfully visualised in Part 2 of this essay. The traditional urban arrangement in Morocco in fact boasts a high degree of refinement and flexibility in the negotiation of the exterior-interior binary. The receptivity characteristic of Moroccan hospitality is reflected in housing structures simultaneously protective of private space and capable of easily and seamlessly embracing the ‘foreigner’ or guest into this space. This is exemplified by the traditional Moroccan riyāḍ (رياض) — an open courtyard or atrium at the heart of the home — which is both the dedicated realm of the women of the house and a highly public space which has, in autobiographical accounts, actually been described as ‘too public’ due to guests constantly ‘invading’.5 Much has been written on the flexibility of traditional Moroccan urbanism and the intricate play of the public-private binary.6 This is a flexibility accorded by spatial thresholds that can bear the nuance of being both separative and inclusive, both individual and communal. And it is a flexibility born of an understanding of self and space as a web of interrelations, a reticulation that emphasises the relationship between things more than the separateness of ‘things-in-themselves’.

In a reticulated structure, every ‘thing’ is hitched to every other ‘thing’ in an overarching whole, so that ‘things’ are indeed only the momentary suspensions of perpetual interrelation.7 Imagine a mosaic of polygonic tiles in which each tile is exactly contiguous with those surrounding it. In other words, it shares directly its boundaries with the boundaries of surrounding tiles. Removing a given tile would lead necessarily to the removal of surrounding tiles until, with ripple-effect, the entire mosaic vanishes. This is how reticulation might be visualised, as a perspective but also as a genuine reality. When we treat ‘things’ as entirely independent of relationship with their surrounds, we get into trouble: the damaging side-effects of univariate medical interventions provide one example; man-made environmental destruction another. From this perspective, the attempt to sever an individual ‘thing’ is not conclusively possible; it is merely an optical fiction, but is often held to be true temporarily in service of some utility.8

Reticulated structure can also be thought of as circular or cyclical structure, because when all ‘elements’ are contiguous, there is no definitive beginning or end, just as in a circle there is no single point of departure. In reticulated wholes, which are also organic wholes, relations proliferate ad infinitum, while straight lines and vertices struggle to fully cleave a given element from its context. The latter attempt ensues, and is indeed functionally necessary, but will always be temporary and deficient.

Islamic ornamentation invites us to try and fail: the eye, the so-called ‘masculine gaze’ (of which both the human male and female is capable), hungry for capture, grasps at a given geometrical element and attempts to fix its focus. But the contiguity of that element with its neighbouring elements will, like a seductress, overwhelm the gaze and lull the senses into rapture, so that the visual becomes the synesthetic, rigid observation becomes embodied contemplation, and individuated figures become a reticulated whole. Of course the point is that both the ‘thing’ (element, part) and the ‘relations’ (whole) that constitute it exist simultaneously. The fact that complete capture, or total individuation, fails does not mean that the ‘thing’ has no reality or value. It simply means it cannot exist without its relationship to every over ‘thing’ and to the overarching whole. In this picture, indeed, the ‘thing’ derives its value; it derives its life.

Reticulated structure is a feminine structure: it is the creativity, dynamism and fertility born of lines flexible enough to bear metamorphosis; lines that are in fact thresholds, relations, facilitating transition and coalescence, rather than fixing boundaries and divisions. The latter is the work of the masculine: the demarcation of identity and difference, the forces of objectification and ownership, the tactics of capture.9 The masculine serves an indisputably crucial and desirable function, since the feminine circularity of incessant self-production and self-destruction cannot maintain a ‘product’ without wedding with the masculine force of capture. This is, of course, the story of procreation itself. The menstruating female perpetually begins and ends life, prepares and sheds it, creates and annihilates its possibility. For life to take proper form, this process must be halted, captured and limited, by male intervention. Without masculine counterbalance, the feminine, the eternal joy of becoming, can never finalise and fix a product, because it necessarily ‘involves in itself the joy of annihilating’.10

The feminine is the incessant circle, the masculine the static square. Islamic architecture exemplifies this binary and its complementary union — the union of plane and spheric surfaces11, of two geometric orders: ‘the order of the square (or the cube), and the order of the circle (or the sphere), the first one representing the static material world and the second one symbolizing the rotation of the universe around its immaterial origin.’12

Feminine and masculine forces are not limited, respectively, to human females and males, but they do find exemplary manifestation in each. In other words, while affirming the “contrasexual” elements of each13, it is nonetheless true that women are nature’s emissaries for femininity, just as men best incarnate masculinity. The fact feminine energies exist in varying degrees in men, and can indeed characterise entire communities and civilisations, is not an argument against the binary demarcation of gender. The inverse applies for masculine energy. Men and women are more similar than different, but the ways in which they do differ (biologically and psychologically) are highly consequential.14 The human female, the woman, is naturally more inclined towards a relation-orientated perspective, and reticulated structure best represents and expresses her nature: she deals better with relations (especially inter-personal relations, people) than with fixed ‘things’, and this befits the demands of matrescence and motherhood.

The human male, the man, on the other hand, is inclined more towards things and their mechanisms.15 The male gaze can, indeed, be objectifying — perhaps the sole sentiment a postmodern reader will grant me. But, I digress: objectification is not necessarily evil, just as “patriarchy” is not equivalent to oppression, and is not inherently bad.16 Indeed, the masculine orientation towards things serves the function of demarcating possession, which is a necessary precondition for individuation, protection and stability.

The masculine is undesirable only when it over-weans itself: when it divorces from complementary (not conflated) union with the feminine, or when it fixes the feminine too rigidly that all growth is asphyxiated. Overly abstract, artificial and de-humanising urban spaces, including inflexible rectilinear structures like tollways, manifest some of the negative extremes of masculine capture, as well as unholistic (uni-variate) interventions into human and ecological health, mentioned earlier. On the other hand, laissez-faire use of birth control and abortion, unchecked emotional self-indulgence and solipsism, as well as radical neo-paganism, can demonstrate some of the negative extremes of femininity (and can, as already noted, be practiced and endorsed by both women and men, and by entire societies and civilizations).

The binary and the consequence of its imbalance is age-old: it is, for example, the very subject of Euripides’s The Bacchae, in which the Thebian kingdom, headed by king Pentheus, is punished by Dionysus for its excessive, untempered masculinity and its rejection of feminine input. The punishment climaxes in feminine (maenadic) hysteria, commensurate in its excess, wherein Pentheus is dismembered and devoured by his own mother in the gruesome rites of sparagmos and omophagia, demonstrating what femininity looks like when taken to its untempered extreme (incessant becoming, production and destruction, birth and death, with no stable being — hence the mother destroys her son, her own creation).

In the contemporary context, the imbalance is patent: in excessive sexual license and over-saturated sexual stimuli, where sex has been so severed from the framework of marriage that the opposing energies of the feminine and masculine are increasingly dis-incentivised to collaborate beyond the sexual act to develop a genuine product (the child produced and raised in stable marital union is the product of proper sexual reconciliation, whereby the dual poles of feminine and masculine are held in productive, healthy tension for the benefit of something larger than their individual whims: the family and, thereafter, the society.) Closely related is women’s increasing participation in pluralised, uncommitted sexual practice, and the damage incurred by offspring as a result — the higher likelihood of fatherless and dysfunctional upbringing, and the overuse of interventions like birth control (the pill suppressing and distorting normal cycles of fertility) and abortion, both of which enact the negation of potential or real progeny.17 This is especially egregious when it is celebrated as an index of progress and ‘women’s liberation’, rather than simply permitted for genuine incidents of need, and invokes the perennial image of the maenadic mother devouring her own child. In these cases, the woman’s maenadic freedom outweighs her infant’s right to life, rather than being mediated by the framework of marriage and motherhood in which femininity is checked and balanced by masculinity and vice-versa (before the detractors detract: of course, marital union with the biological father is not always possible; but even the single mother, when committed to the raising rather than abortion of her child, is checked by an inter-relational framework in which her ‘freedom’ is not more important than the freedom of her child). Perhaps most concerning is the increasingly rife social-constructionist ideology of non-binary gender, whereby people not only feel, in small numbers, but are taught at large that men can be women and women, men — a life-negating equation that points to the dysfunction of the foremost life-producing binary.

There is nothing uniquely Moroccan about reticulation. It is a primordial structure. The kind of individual and cultural perception which acknowledges and expresses this structure — a relation-orientated perspective — might be called sacred or ‘tertiary’ perception,18 and that which forsakes it, believing it truly can pull a ‘thing’ from its whole and explain it by means of its own self-positing properties (as a thing-in-itself), might be termed secular or abstract perception.19 In Morocco it is the acknowledgment of reticulated structure, in cultural consciousness as in quotidian practice, which stands out. This coincides neatly with the spirit of solidarity that characterises ‘collective’ cultures like Morocco, and is expressed powerfully in Islamic art and architecture.20 But it can also be comprehensively grounded in the lived, quotidian reality of Moroccans, since it structures familial and social life.

The second half of this paper is dedicated to these everyday examples of reticulation in Morocco. But I would like, first, to weave together the various skeins of discussion so far introduced:

The acknowledgement and expression of reticulated structure — a relation-orientated approach to life — is a feminine morphology. It privileges relations over things, communal over individual identities, the whole over its parts. Because these characteristics are so observable and palpable in Morocco, it is not a great task to prove, despite dominant misconceptions, that Moroccan society is, also, fundamentally feminine.21 In other words, femininity as a life-force has significant structuring-power in Morocco, which encourages us to challenge dominant perceptions of it and other Muslim-majority societies as totally “male-dominated”. Or rather, it encourages a critical distinction between masculinity and patriarchy, one which acknowledges that patriarchal structure does not necessarily mean the over-weaning dominance of masculinity, but can in fact function in the interests of femininity, allowing it to flourish. This distinction is consequential, because the use of the concept of “patriarchy” often conflates it, whereby it refers both to “A social system, governed by men, in which the father is the head of the family” and to “Dominance of a society by men, or the values that uphold such dominance.”

Highlighting the feminine morphology of Moroccan social structure is consistent with the elevated importance of the family, the care-giving roles of women, the domestic space and, more broadly, the relation-oriented (feminine) approach to perception and practice, which spills out of the home onto the streets of public life and is actioned also by men. Reticulated selfhood is, as already emphasised, not limited to the human female, even though she best incarnates it. The ‘empirical’ examples in the second half of this paper are not gender-exclusive, they rather characterise the whole society.22 In other words, femininity expresses itself spatially in Morocco through an inter-relational understanding of the self — of the individual, thing, element as irrevocably contiguous to and contingent on the dynamic bodies around it.

For authentic illustrations of reticulated structure in Morocco, please continue on to Part 2 of this essay.

Fajr: the first of five Islamic prayers during the day, occurring just before sunrise.

Khalti: “my auntie”, but also used generally as a respectful form of address older women.

Despite the division of the once singular residence, the family downstairs feels like an extension of our own; indeed Rayān, my host family’s grandson, and Abdul-Samad, one of three children from the family below, are constantly running up and down the stairs between the two homes; they are more like brothers than friends on a play-date. The extended family structure has, therefore, lived on in spirit.

ḥarsha: a Moroccan flatbread made with semolina.

Fatima Mernissi, The harem within (London: Doubleday, 1994) 87, 5.

Stefano Bianca, Urban Form in the Arab World: Past and Present (London: Thames & Hudson, 2000).

Otherwise phrased, moments of being in the process of becoming. Becoming is, however, contained within the whole of nature, or of God, in the way that the full growth of a plant is contained within its seed. It is not an anarchic becoming that finds no ultimate sublimation. See Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, “Observations on Morphology in General,” in The Essential Goethe, ed. Matthew Bell (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018).

The optical fiction of the ‘thing’ is transcribed by the linguistic fallacy of the ‘noun’ — which is not to say that ‘things’ do not exist, but that their interpretation and description as completely independent or self-positing is illusory (though often has utility). The noun accords permanent individuation to a perceived ‘thing’ whose boundaries, in contextual reality, are enmeshed with a whole host of other ‘things’, so that these things are, ultimately, only qualities and gradations of the same ultimate ‘Thing’ (God) in its process of becoming.

Binaries often conceal as much as they reveal, but I do not think therefore that their value is defunct. After all, the condition of life itself is a sexual binary. The juxtaposition that I draw, then, between the masculine and the feminine may sound simplistic, but I believe it is a productive and in many ways very real framework within which to further explore nuance. Complete truth is always a few breaths away from the close of a sentence, but it is sentences with which we are dealing here.

Friedrich Nietzsche, The Twilight of the Idols; Or How to Philosophise With a Hammer, (London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1899), section 235.

Bianca, Urban Form in the Arab World, 45.

Ibid., 46.

See Jung’s famous anima and animus.

Jordan Peterson, “The Gender Scandal – in Scandinavia and Canada,” National Post, Dec 11, 2018. https://nationalpost.com/opinion/jordan-peterson-the-gender-scandal-in-scandinavia-and-canada.

Rong Su, James Rounds and Patrick Ian Armstrong, “Men and Things, Women and People: A Meta-Analysis of Sex Differences in Interests,” Psychological Bulletin 135, no.6(2009): 859-884. doi: 10.1037/a0017364.

The essential qualities of patriarchy are critical and life-affirming: the protection and provision of male leaders, from the domestic scale (the husband, father) to the political (the tribal leader, king, military and governmental apparatus). The simple biological fact is that women are both vulnerable and preoccupied in pregnancy and in the caretaking of dependents, and also on average less physically strong (their physical subtlety befits them as mothers), and therefore require invested, trustworthy and competent males to fortify their space. This is patriarchal structure at its core; tyranny and misogyny are its extremities, not its essence.

My critique here is not of the pill or abortion per se, but of their ‘overuse’ and the excessive and indiscriminate dependence on them — as explicitly indicated.

Sara Sviri, “Seeing with three eyes: Ibn al-cArabī’s barzakh and the contemporary world situation,” Synthesis Philosophica 62, no.2 (Jan 2016), doi: 10.21464/sp31212.

Great minds have dealt with these opposing forms of perception for centuries: Nietzsche described them within the framework of the Dionysian-Apollonian dichotomy (See Friedrich Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy); in more recent times, Ian McGilchrist has comprehensively traced their anatomical, psychological and social manifestations within the framework of the right-left hemispheric divide in the brain (See Ian McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary).

Titus Burckhardt, “The Void in Islamic Art,” Studies in Comparative Religion 16, no.1 & 2 (Winter-Spring, 1984), http://www.studiesincomparativereligion.com/Public/articles/The_Void_in_Islamic_Art--by_Titus_Burckhardt.aspx.

I am not pitching a dramatic counter-claim that femininity overrides masculinity in Moroccan society. The reality is in fact a more-or-less productive balance between the two. The emphasis on femininity intends, however, to compensate for skewed and facile interpretations of Morocco as invariably “male-dominated”. Indeed, a society in which feminine energy operates optimally is one in which, by default, masculine energy can also function healthily, since life itself is produced by their reconciliation. Equally, the degradation of both feminine and masculine inclinations goes hand-in-hand, and one need not dig too deeply to observe this in action today in parts of the globalised West. In Morocco, even in its cosmopolitan capital Rabat, the normative maintenance of sex-exclusive spaces, roles, and identities shows a society defending a perennial binary, in the face of forces intent on its conflation and defeat — which is, in the end, nothing less than a death-drive.

Where ‘characterisation’ entails distilling the essence, the majority dynamic, not accounting for every nuance.

Penelope, what a sublime essay you’ve written. I plan to reread this aloud to my husband so we can discuss it and enjoy its contents together.

Great piece! Really appreciated this, and will be including it in the February Bazaar at Stranger Worlds. Is it your preferred choice to go simply by 'Penelope' or can I include a surname in crediting you...?

With unlimited love,

Chris.